Why the targeting of Russia’s so-called “Shadow Fleet” represents a most dangerous escalation of NATO’s proxy war on Russia.

By Eamon Dyas

There are many ways in which a country’s sea-borne trade can be curtailed by an enemy. The most obvious one is the use of a close naval blockade which restricts all shipping to the enemy’s ports. There is also the option of a distant blockade – the interception of an enemy’s maritime shipping on the high seas that is designed to systematically confiscate the merchant ships and cargoes of an enemy and in the process choke off its capacity to trade with the wider world.

In the context of the Russo-Ukraine conflict, when it comes to its relationship with Russia the west, in the form of the EU, UK and NATO, has chosen not to do this openly as to do so in that way would be tantamount to an act of war. Instead, the west has chosen a different way to impose a blockade and that is through the use of sanctions. Those sanctions which began in 2014 and have consequently escalated through 17 levels of EU targeting of individuals, prohibiting the exportation of machinery and equipment to Russia, curtailing the export of Russian gas and oil and the removing of financial facilities. Through these means the west has attempted to choke off Russia’s capacity to trade with the world.

However, these sanctions have only had a limited impact and, arguably have hurt the west as much as they have Russia. In most instances, because the west is not the entire world, Russia has been able to circumvent these sanctions. This has led to the west using the sanctions in a way which will ultimately present Russia with a choice of directly confronting the means by which the sanctions are being implemented rather than circumventing them. Central to this is the way in which the west has expanded the use of financial tools to coerce Russia.

When it comes to any trading nation one of the areas most vulnerable to financial sanctions is that of marine insurance. We see the early emergence of an awareness of this at the start of the First World War. Sweden was one of the Scandinavian neutral countries during that war and it possessed the third largest marine fleet in the world at the time. At the start of the war the Swedish state sought to protect itself from the fact that one of the belligerents in the First World War, Britain, was the pre-eminent global supplier of marine insurance. The Swedish state was therefore forced to adopt measures which anticipated the withdrawal of insurance cover from its fleet should Britain seek to exploit its position in order to influence Sweden’s behaviour as a neutral which traded with Germany.

“At the outbreak of war Sweden possessed an extensive merchant marine. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, Swedish shipping in the North Sea and the Baltic had made great progress, and regular lines to Great Britain, France, and Germany had been established. The decade immediately preceding the War marked the rise in Swedish transoceanic shipping. Besides, a considerable number of tramp lines had been set going between Sweden and the Mediterranean, America, South Africa, the Far East, and Australia. Exchange of goods could, consequently, be made to a considerable extent in Swedish vessels, which became of so much more importance during the War, as foreign tonnage in an ever increasing degree ceased to call at the ports of Sweden. And the thing that made decisively for a renewal of economic life, after the first stupefaction following upon the outbreak of war was that shipping connections, the arteries for the flow of goods into and out of the country, were again made to function. This could not be done, however, without an organisation of marine insurance, and here the assistance of the State was necessary. In fact, the State took it upon itself to ensure against war, under certain conditions; a Royal Decree was issued on August 17, 1914, and on the same day the State War Insurance Commission was established. Thanks to this intervention of the State and the efforts of Swedish shipowners themselves, life and movement soon was revived in Swedish ports. Shipping was already moving and most actively, in the beginning of September; and it was shaping itself after the conditions created by the War.” (Sweden, Norway, Denmark and Iceland in the World War. Section on Sweden by Eli F. Heckscher. Published by Yale University Press and Humphrey Milford: Oxford University Press for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Division of Economics and History, 1930, p.54).

The author of the above quote, Eli Felip Heckscher, was professor of Political Economy at the Stockholm School of Economics at the time of the First World War. His experience during the war contributed to his conversion from being an exponent of the state’s involvement in the economy to one who championed economic liberalism and opposed state intervention. It also led to the economic theory for which he became famous, the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, a model of international trade that predicts that capital-abundant countries export capital-intensive goods, while labour-abundant countries export labour-intensive goods. A corollary extension of which is that capital-abundant countries are those which are best positioned to utilise the tool of financial sanctions in circumstances of conflict with countries whose economies rely more on trade.

In the end despite Sweden’s efforts to protect its neutrality, after the United States entered the war it combined with Britain to coerce the country into curtailing its trade with Germany. But it did reveal an early example of how a trading nation anticipated and took action against the possibility of being targeted by a country which was capital abundant to the extent that it had a virtual monopoly on marine insurance.

The west’s use of financial sanctions against Russia

The west has been targeting Russian banks and financial institutions with sanctions since 2014 and these have intensified with every sanctions package since then. From very early on the sanctions were also increasingly targeting the capacity of Russia to supply its gas and oil to its markets.

On 24 February 2022 the US sanctioned Sovcomflot, Russia’s largest shipping company and one of the world’s largest ship transporter of hydrocarbons. On 15 March the EU imposed its own sanctions on the company and on 24 March the UK followed suit. These sanctions made it difficult for Sovcomflot to obtain insurance for its cargoes and vessels. At the time the company owned a fleet of 122 vessels which included 50 crude oil tankers, 34 oil products tankers, 14 shuttle tankers and 10 natural gas carriers as well as 10 icebreakers.

In 2022 the EU’s Sixth Sanctions Package (agreed on 31 May and introduced on 3 June 2022) included a partial ban on the importation of seaborne crude oil and petroleum products from Russia into the EU. At the time Europe was Russia’s largest oil customer and purchased almost half of the 4.7 billion barrels produced by Russia each day. The 2022 measures were expected to cut around 90% of oil imports from Russia to the EU by the end of 2022. With oil exports constituting around 40% of Russia’s federal budget these measures were expected to inflict significant damage on the Russian economy and weaken it in its conflict with Ukraine.

However, because there is a wider world beyond Europe it was known that Russia could still access the energy markets of that wider world. As one business law consultancy firm noted:

“The concern with introducing an EU oil embargo in isolation was that Russia would simply look to divert its supplies elsewhere, principally to China and India, who have both increased oil purchases from Russia within the last few months and are importing record levels of crude.” (Impact of UK and EU and UK ban on Russian oil and insurance, Reed Smith Client Alerts, 1 June 2022).

For that reason, together with the oil embargo,

“The EU also intends to impose a ban on EU insurers providing coverage for vessels carrying oil shipments from Russia. By all accounts (and according to reports), the insurance ban has been coordinated by the UK government and will result in Russia also being shut out of the crucial Lloyd’s of London insurance market, which will significantly impact Russia’s ability to export its oil.” (Ibid.)

And this combined EU and UK measure

“means that Russia’s ability to export oil anywhere in the world will be heavily disrupted. Shipowners will now struggle to find alternative cover as P&I Clubs cover around 90% of the world’s fleet.” (Ibid.)

On the other hand, it was accepted that

“Sovereign guarantees” [similar to the one introduced by Sweden during the First World War – ED] could be an option as could using smaller insurance markets with less established brokers, but there is still the question of whether ports would accept vessels with cover from anywhere outside of the International Group of P&I Clubs.” (Ibid.)

These measures, alongside the removal of Russian banks, (Sberbank, Credit Bank of Moscow and the Russian Agricultural Bank, etc.) from the SWIFT system, were adopted by the EU on 3 June 2022.

Although dismissed in western media reports of the surrounding events, the questions of payment and insurance cover were important element in the negotiations in what became known as the “grain deal” which Russia signed with Turkey and the UN on 22 July 2022. This deal was signed in the midst of a concerted western media campaign which pointed the finger at Russia’s blockade of Odessa and the prevention of Ukraine’s grain exports as the cause for the rise in grain prices which was adversely impacting the poor in Africa. In this way the plight of the poor of Africa was heavily portrayed as the victim of Russia’s aggression in Ukraine.

Maritime insurance and the “grain deal”

This deal highlighted in practical terms the obstacles that the US, EU and UK had imposed on the capacity of Russia to ship its produce (aside from oil, grain and fertiliser) to its markets. The deal made between Russia, Turkey and the UN involved a guarantee of the safe navigation for the export of Ukrainian grain and related foodstuffs through the Black Sea and a concurrent agreement to guarantee the unimpeded exports of Russian food, fertiliser and raw materials through the Black Sea. The main impediment for these Russian exports at this time were the knock-on effect of the removal of Russian banks from the SWIFT international payment system and the reluctance on the part of the west of recognising insurance cover supplied from Russian sources in response to the refusal of western insurers to do so.

Under the agreement the impediment relating to the lack of access to SWIFT was to be overcome through an arrangement by which the payment for Russian exports of food, fertilisers and raw material was facilitated via payments made through the intermediary of J. P. Morgan using the SWIFT system. The problems associated with the issue of marine insurance was initially overcome by a recognition by Turkey, India (the Indian Registry of Shipping had announced on 23 June 2022 that it would issue safety certification for several dozen Russian-managed ships) and China of marine insurance supplied to Russian ships from Russian sources. At the time everyone knew that these were temporary measures but with the possibility of them being extended for as long as the agreement lasted.

The grain agreement was originally meant to last for four months and due to expire on 19 November 2022. Before the expiry date, on 17 November, the Turkish president Erdoğan announced that Russia had agreed for the deal to be extended for a further 120 days with a new expiry date of 18 March 2023. Shortly after this extension came into effect on 19 November, the Russian Deputy Transport Minister, Alexander Poshivay reminded reporters of the core issues that remained beyond the agreement and for which a remedy would need to be found if the agreement was to continue:

“The issue [of recognising Russian insurance] will have to be worked out with the entire world”, he said.

“He said that at present, ships sailing under the Russian flag and denied insurance by Western companies were being insured by Russian insurance companies and reinsured by Russian National Reinsurance Company (RNRC). The insurance coverage of Russian insurance companies includes all maritime transport risks in accordance with international requirements, and ‘Russian insurance has already been in use for many months.’

“RNRC has ‘increased its charter capital to 750 billion rubles, but now it is actually practically unlimited. The Central Bank is a guarantor for RNRC, that is, guarantees [for reinsurance] can be applicable to any volume of Russian oil and oil products. Practice is needed for success,’ Poshivay said. RNRC is a Central Bank subsidiary.” (Turkey recognises Russian insurance for shipping by vessels, India also for the most part, Interfax, 29 November 2022).

He went on to say:

“With the imposition of sanctions, insurance services in West Germany are no longer available to Russian maritime carriers. According to established practice, those services were provided by European and American companies. In addition, difficulties have arisen due to a significant increase in the cost of sea transportation, the non-recognition of insurance certificates issued by Russian insurers and the RNRC after Lloyd’s syndicates declared Russian waters to be a zone of war-related peril.” (Ibid.)

These issues were of course omitted from the western media’s reporting at the time. But they became critical to the continuation of the grain deal beyond its extended 18 March 2023 deadline. As the new expiry date loomed Russia said it was prepared to continue the arrangements that guaranteed a continuation of the Ukrainian exports but needed a guarantee that its own agricultural exports would continue to enjoy the protection of the payment arrangements underwritten by JP Morgan using the SWIFT system that had previously been in place.

But the US was increasingly concerned that the indefinite continuation of the arrangements with J. P. Morgan would soften the impact of its wider denial of Russian access to the SWIFT system. Consequently, as the March deadline approached the US showed no real willingness to continue the arrangements which had made the two previous agreements possible. In fact, the US, by denying that Russian agricultural exports were being hindered by its exclusion from the SWIFT arrangements was implying that Russia was merely using this as an excuse for abandoning the agreement with no good reason. But that assertion ceased to retain any credibility when J. P. Morgan, which had been arranging the payments to the Russian agricultural bank through the SWIFT system, stated that the US State Department would have to act on this issue if it were to continue to function. Needless to say the US State Department took no further action to ensure its continuance.

With regard to the question of the recognition of Russian-sourced maritime insurance for the ships involved the EU was to do its part in ensuring that the grain deal would go no further than the March 2023 deadline. In February 2023, on the first anniversary of Russia’s Special Military Operation and a mere month before the expiration of the latest extension to the grain deal the EU in its 10th package of sanctions targeted the Russian National Reinsurance Company (RNRC). In this single act the EU guaranteed that Russia would be in no position to extent the grain deal beyond 18 March.

On addressing the inclusion of RNRC in its 10th package of sanctions the EU explained:

“This reinsurance service offered by the RNRC has enabled the Russian Government to deflect and mitigate the impact of western sanctions on its oil trade – which provides a substantial source of revenue to the government of the Russian Federation.

“The Bank of Russia has increased the authorised capital of its subsidiary RNRC from 71 billion rubles ($934 million) to 300 billion rubles since Russia’s incursion into Ukraine. Various other sources, including those citing Russian government officials, confirm that RNRC has reinsured oil cargoes flying the Russian flag that have been denied insurance by western businesses.

“Therefore, the Russian National Reinsurance Company is an entity supporting materially and financially, and benefitting from the government of the Russian Federation, which is responsible for the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of Ukraine. Moreover, the Russian National Reinsurance Company is an entity involved in the economic sectors providing a substantial source of revenue to the government of the Russian Federation, which is responsible for the annexation of Crimea and the destabilisation of Ukraine.” (Lloyd’s List, 24 February 2023).

Attempts to re-establish the grain deal arrangements were made throughout the summer with Russia signalling that the deal could be restarted if its disagreements could be resolved but all these proved futile.

But it wasn’t only the financial mechanism by which Russia’s sea trade was being hampered. The EU’s 10th sanctions package also attacked the logistics by which its shipping was managed. Also sanctioned in that package was Sun Ship Management Ltd. This was a ship leasing and management company that was formed in Dubai in 2012 and owned by UAE and Russian nationals and managed by multinationals. The EU claimed that the company was part of the Russian company PAO Sovcomflot which had been sanctioned the previous year.

The United Kingdom followed suit when it also sanctioned the Dubai company. In justifying its action the UK alleged that in April 2022 shortly after the start of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict and the imposition of western sanctions, Sovcomflot had transferred control of about 90 of its tankers and LGN carriers to Sun Ship Management. Sovcomflot denied that there was any such connection between the two companies and that Sun Ship Management was an independent company whose services and resources Sovcomflot purchased when necessary. In that context it should be added that it was not unusual for a large shipping company to use a shipping broker like Sun Ship Management to “rent out” its ships in just the same way that an estate agent is used to rent out a landlord’s properties. In the course of its active life a shipping vessel may have been leased and sub-leased several times through the use of a shipping broker.

However, the UK was not prepared to accept any such business arrangement as legitimate when the Russian ship owner Sovcomflot was involved. The UK insisted that the company was involved in transporting Russian oil in breach of the sanctions. This in turn was denied by Sovcomflot when it issued a statement that “the activity of Sun Ship Management (D) Ltd is completely legitimate because no vessels are carrying their cargoes into the EU unless expressly permitted by EU respective regulations.”

This last reference was to the fact that Europe, to some extent, continued to be reliant on Russian oil and was compelled to permit some instances where the oil was carried in Russian vessels – at least in 2023.

The EU’s 10th sanctions package also included the sanctioning of a company called Atomflot. This was a Russian company that maintained Russia’s icebreaker fleet which is critical to the transport of oil along Russia’s Northern Sea Route. The company appears to have been a last-minute inclusion in the sanctions package and came a week after Putin gave a speech to the Russian Federal Assembly in which he announced:

“Our plans include the accelerated modernisation of the eastward railways, the Transit and the BAM, and building up the capacity of the Northern Sea Route. This means not only additional cargo traffic, but also a basis for addressing national tasks on the development of Siberia, the Arctic and the Far East.”

As a Lloyd’s List report stated:

“With oil and gas exports shifting from Europe to Asia as a result of Russia’s military action against Ukraine and subsequent western sanctions, Russia’s icebreaking fleet is key to the country’s Arctic hydrocarbon strategy.

“In order to escort oil and gas tankers on the much longer and more challenging voyage from the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas to Asia, rather than the much shorter and less icebound routes to Europe, Russia relies on Atomflot’s fleet of nuclear icebreakers.” (EU sanctions Russian tankers, re-insurance and ice breakers, by Richard Meade, Lloyd’s List, 24 February 2023).

Undoubtedly this will have implications for the expansion of the ongoing proxy war between the west and Russia as it has implications for Russia’s interests in the Arctic. With Russia about to make increased use of the Arctic route for its LNG exports using four ice class category Arc4 vessels (built in 2023 and 2024 after Putin made the above speech) and the EU having sanctioned them in December 2024 as part of the ‘shadow fleet’ the prospect of the Arctic becoming another area of potential conflict has only increased. (Sanctioned ‘shadow fleet’ gas carriers prepare for shipments on Arctic route, by Atle Staalesen, Barents Observer, 28 May 2025).

The Price Cap

By 2023 the US, EU and UK had constructed the means by which the cost of moving Russian oil was artificially inflated to the point where that cost would make it impossible for Russian oil producers to make a profit. This was being done by the denial of Russian shipping to western insurance systems, the sanctioning of ships carrying the oil, the sanctioning of shipping logistics companies that managed the shipping arrangements, and the denial of access to the SWIFT system by Russian banks therefore making it difficult for payment to be made to the oil companies in dollars. But there was also the practice of interfering directly with the natural operation of the oil market through the imposition of a price cap on the sale of Russian oil.

This policy was decided at the meeting of the Finance Ministers of the G7 group on 2 September 2022. The cap was set at $60 a barrel on 3 December 2022 and came into effect on 5 December. On 4 November 2022, before the policy was finalised the UK Treasury confirmed what this would mean in practice.

“By December 5, tanker owners that fly any European Union flag or carry P&I insurance from an EU or UK club can no longer have crude oil onboard that originated in Russia, unless Russia has sold the crude to the buyer at or under a price cap pushed for by G7 members. The US is expected to join the insurance ban shortly meaning more than 90% of the world’s insurers will shun Russian-linked crude tanker business from next month.” (UK confirms it will not insure ships carrying Russian oil, by Sam Chambers, Splash247.com, 4 November 2022).

This represented a new departure as the threat of sanctioning was no longer restricted to Russian ships but to any ship which was deemed to be transporting Russian oil above the price cap even if those ships were sailing under an EU flag or operating under what would otherwise have been accepted as legitimate western insurance certification. By using a price cap in this way to define what the west decided was a legitimately trading commodity it was in effect establishing a virtual rather than a physical blockade on Russian oil. The ostensible purpose behind this was to restrict the flow of money to the Russian treasury by ensuring that the price that its oil could fetch was kept at a level that either meant a loss or at least a significant diminution of the profit margin.

Because there was no previous example of a price cap being used in this way it generated much controversy and was subject to early scrutiny. One of the earlier assessments of its impact was in a report by Benjamin H. Harris in a specialist publication named Russia Matters. Harris was a member of the Brookings Institute and had been chief economic advisor to Joe Biden when he was vice-president. In that report Harris quoted the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air’s Russia Fossil Tracker which stated that:

“the volume of crude exports has been stable overall, experiencing only minor shifts following a modest dip in March and April 2022. For example, in the month prior to the invasion, Russia exported an average of around 700 million metric tons of crude daily, falling to approximately 560 million metric tons in the first half of April 2022, as global trade routes were reshuffling, before climbing to an average of about 740 million metric tons from May 2022 through today [September 2023 – ED]. Exports of oil products have been similarly stable, generally within 150 million to 250 million metric tons per day from May 2022 through the current period.” (The Origins and Efficacy of the Price Cap on Russian Oil, by Benjamin H. Harris, Russia Matters, 14 September 2023).

In other words, in the first nine months of its operation the price cap had little effect on the volume of Russian oil that continued to be shipped. Harris himself observes that the price cap produced another outcome:

“A second outcome is the dramatic change in the composition of importers of Russia oil, with a marked elongation in the distance travelled to reach new export destinations. The shift is nothing short of remarkable. Prior to the invasion, the bulk of Russian fossil fuel exports – roughly 55% – was exported to the EU, with China comprising another 18% or so and India taking only 1-2% of these products. By January 2023, these trade relationships had shifted considerably. The share of Russian fossil fuel exports going to the EU fell to just 20%, and that share would be halved to about 10% by summer 2023. China, India and Turkey would instead assume these barrels, with these three nations now importing about two-thirds of Russian fossil fuel exports.” (Ibid.)

But Harris points out that

“An important consequence of these new trade patterns is dramatically higher shipping and insurance costs. The precise increase in these costs is not well-documented but is likely due to a combination of factors. Perhaps the most obvious is the higher cost associated with longer trade routes; a voyage to Indian and Chinese ports takes about 16 to 18 days – compared to prior voyages of four to six days to European ports. Another factor for the higher costs is a ‘sanctions premium’ that drives up the per-mile cost of shipping and insuring Russian-origin oil above-and-beyond the price charged to other exporters. According to one report, the combined impact of these factors meant that an excess of one-third of a Russian oil shipment’s value was captured by these higher costs.” (Ibid.)

What Harris is pointing to here is the impact of the combined strategy of banning Russian oil from European markets, sanctioning Russian shipping, denying it access to the main marine insurance markets, banning Russian banks from access to SWIFT, and imposing a price cap on the price of Russian oil on the global markets.

The result of all of this was that, despite Russia being able to sustain the volume of oil exports, the revenue accrued from the sale of that sustained volume has been diminished. In fact, one of the arguments that was used in favour of the price cap was that even if Russian oil managed to circumvent western checks to reach alternative markets the fact of the price cap would itself influence the available market by setting a level around which discounts would be negotiated. However, those negotiations would also take place in the context of the real market price for oil and in circumstances where the price charged from other oil suppliers was higher than the G7 price cap then the likely return for Russian oil would also be higher than the $60 a barrel – how much more would depend on how much the real market price exceeded the price cap. The same would apply if the real market price of oil was low, only in those circumstances the pressure would be to produce a lower income than the $60 price cap.

In fact this is what appears to have happened in the initial period of the operation of the price cap. In other words “the decline in the global price of oil, led the U.S. Treasury Department to cite reports from the Russian Finance Ministry that its oil revenue had fallen by over 40% in the first quarter of 2023 relative to one year earlier.” (Ibid). Since then the price of oil has increased with a commensurate improvement in Russia’s income from oil exports.

This and other countermeasures introduced by Russia has largely muted the initial impact of the price cap. As early as September 2023 Harris identified one of these countermeasures:

“Russia’s countermeasures, which include expanding the fleet of ships available to transport oil around the price cap, will require close monitoring and strict enforcement to maintain this level of depressed revenue moving forward.” (Ibid.)

Since then there had been growing voices demanding that the price cap be lowered and a more assertive policy adopted by the west towards the “Shadow Fleet” which was seen as the main reason why the price cap has not worked as hoped.

The initiative for this appears to have come from the Nordic and Baltic countries at the start of the year. A letter sent jointly by the Foreign Ministers of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania and Sweden to the European Commission’s High Representative on Foreign Affairs, Kaja Kallas, and the European Commissioner for Financial Services. Maria Luis Albuquerque, on 11 January 2025 called for a reduction in the price cap and a more vigorous policy towards the “shadow fleet”. (Nordics and Baltics ask EU to tighten price cap on Russian oil, Euronews, 13 January 2025). This has led to a more vigorous policy being adopted of late:

“Both the UK and EU vowed this month to further increase the pressure on the Russian oil sector in an effort to reduce revenues and support to the Russian economy. The EU noted it doubled the number of tankers it had sanctioned to over 300 vessels while the UK added another 100 to its listing. The UK said it was in discussion with Western allies about lowering the price cap the G7 imposed on the sale of Russian oil.” (Western Sanctions Take Big Bite Out of Sovcomflot’s Results, Maritime Executive, 23 May 2025).

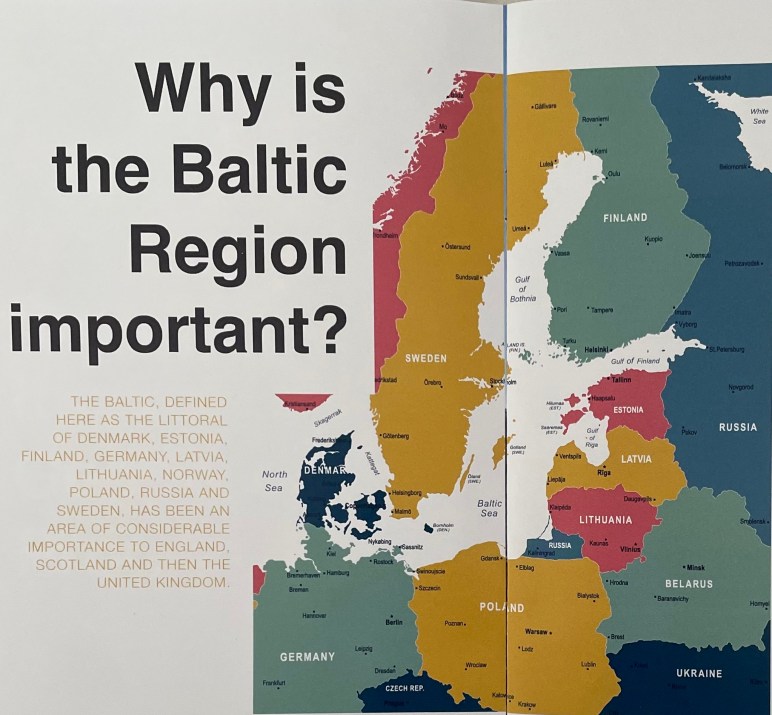

However, all of this has established a momentum which will only increase the prospects for a direct confrontation between NATO and Russia in the Baltic Sea. [The map above shows the location of the Baltic Sea, north of Poland]

The push to confront the “Shadow Fleet” in the Baltic Sea

These developments in terms of the implementation of the price cap and the curtailment of Russia’s “shadow fleet” take place in the context of the inflated reporting of incidents in the Baltic Sea involving cable damage and alleged nefarious activities on the part of Russian vessels.

In January 2025, around the time that the Foreign Ministers of the Nordic and Baltic members of NATO wrote to the European Commission asking for a lowering of the price cap on Russian oil and complaining about the continuing activities of the “shadow fleet” NATO announced that it was setting up a new organisation called the Baltic Sentry Mission. The justification for this was the several alleged but unproven claims that several cables under the Baltic Sea had been damaged or deliberately severed in 2024. This mission would involve the use of more patrol aircraft, warships and drones and as the BBC reported at the time: “While Russia was not directly singled out as a culprit in the cable damage, [NATO chief -ED] Rutte said NATO would step up its monitoring of Moscow’s “shadow fleet”. Rutte was further quoted as saying

“there was reason for grave concern” over infrastructure damage, adding that NATO would respond to future incidents robustly, with more boarding of suspect vessels and, if necessary their seizure.” (Sweden seizes ship after suspected Baltic Sea cable damage, BBC, 27 January 2025).

In the same report it was revealed that Sweden had seized a ship suspected of damaging a data cable running under the Baltic Sea to Latvia with the Swedish authorities claiming that its initial investigation pointed to sabotage against the ship, the Vezhen, which was being held in a Swedish port. This incident, as was the case with others, received much publicity in the western media at the time. However, like the other incidents, it turned out that the Vezhen – a cargo ship owned by a Bulgarian company – had not been guilty of sabotage and the cable had been damaged accidentally.

According to the trade journal Oil Price:

“Russia’s shadow fleet consists of approximately 500, mostly poorly insured and aging tankers that ship crude to countries such as India and China, in defiance of Western sanctions. These tankers, estimated to carry as much as 85% of Russia’s oil exports—which bring in a third of Russia’s export revenues—typically have opaque ownership structures and lack top-tier insurance or safety certification. Most belong to anonymous or newly formed shell companies based in jurisdictions such as Dubai, further complicating accountability.

“The majority of shadow tankers sail across the Baltic Sea, a route considered critical for Russia’s energy exports. The shadow fleet uses various tactics to avoid detection, including ship-to-ship transfers in international waters, spoofed location data, and fake ship identification numbers. Some estimates suggest that approximately three shadow tankers carrying Russian crude pass through European waters each day, including the Danish straits and the Channel. Some experts estimate the shadow fleet may now include as many as 700 tankers.” (Will Europe’s $50 Russian Oil Price Cap Plans Thwart the ‘Shadow Fleet’?, by Alex Kimani, Oil Price, 20 May 2025).

With the various measures put in place to destroy the capacity of Russia to trade in oil it has been forced to adopt countermeasures that include what is described as a “shadow fleet”. Lloyd’s List describes the vessels that constitute this fleet as a ship that is over 15 years old and not insured by a western endorsed insurance company. This does not mean they are not seaworthy. There are many tankers that are more than 15 years old that are not considered to be candidates for the definition of “shadow” or “dark” because they hold western endorsed insurance certification. They are thus defined because they exist outside the western insurance umbrella. However, that in itself had not been an issue in the past when Russian insurance was accepted as legitimate. It is not so much the age of the vessels that is the issue but rather that they sail in defiance of the arbitrary prohibition of western powers – powers that have weaponised their financial tools to stop Russian trade.

With Russia being compelled to increase its fleet to convey oil to its far-flung markets (the 16 to 18 days it takes to deliver to China and India against six days to its old European markets means that it inevitably needs more ships) and with sanctions obstructing its ability to procure ships by conventional means, Russia has been forced to use this “shadow fleet” as an alternative means to transport its oil to its customers. The main transit route of this “shadow fleet” is the Baltic Sea.

The increased presence of NATO in the Baltic Sea and the pressure to curtail Russia’s “shadow fleet” is inevitably creating a situation where there is a real danger of a confrontation between NATO and Russia in the area.

Should NATO forces in the Baltic Sea decide to act as policemen for the implementation of the price cap then its brief will extend beyond the mere monitoring of the “shadow fleet” in the context of possible cable damage such a situation could easily escalate to one where NATO is seen to be operating a physical blockade in fact if not in name and it would be foolish not to expect Russia to respond accordingly.

The pressure for NATO to adopt that role is compounded by the limitations within which the Baltic states view their capacity to intercept Russian vessels in the Baltic Sea:

“Lithuanian National Security Advisor Kęstutis Budrys has highlighted the ambiguity surrounding the law on interdiction in international waters, warning that trying to stop the shadow fleet could risk an all-out military confrontation with Russia. Last week, a Russian fighter jet briefly entered Estonia’s airspace, in what some experts suspect was a reprisal for the Estonian military escorting a tanker named Jaguar out of the country’s economic waters. The Estonian navy acted quickly, believing the ship posed a threat to nearby underwater cables, and checked its status and registration. The Russian jet entered Estonian airspace without permission.” (Kimani, op. cit.)

In fact Kęstutis Budrys, aside from his role as National Security Adviser is also Lithuanian Minister of Foreign Affairs. With Russia viewing its Baltic Sea route for its “shadow fleet” as critical to its ability to trade its oil with the outside world the behaviour of NATO and the Baltic states in the Baltic Sea could easily become a trigger for a wider confrontation.

In this context it is worth noting that Britain has been the main cheer-leader for stronger action against the “shadow fleet”. In a visit to Oslo on 9 May Starmer, in announcing the UK’s latest sanctions against Russia said:

“The threat from Russia to our national security cannot be underestimated, that is why we will do everything in our power to destroy his shadow fleet operation, starve his war machine of oil revenues and protect the subsea infrastructure that we rely on for our everyday lives.” (“We will do everything in our power to destroy Putin’s shadow fleet”, by Atle Staalesen, Barents Observer, 15 May 2025).

The UK measures included the sanctioning of 101 ships, mostly oil tankers which it defined as being part of the “shadow fleet”. At the same time the EU announced its 17thsanctions package and that included measures against 189 “shadow fleet” vessels with the ex-Prime Minister of Estonia and now the EU’s representative for Foreign Affairs and Security, Kaja Kallas saying that the new package “will target more of Russia’s shadow fleet, which is illegally shipping oil for revenues to fund Putin’s aggression”.

Needless to say, the voices from Kiev are among those pushing for just such an outcome. The Sanctions Programme at the Kyiv School of Economics has been in the forefront in compiling lists of ships which it claims are part of Russia’s “shadow fleet” and demanding that the west takes action against them. Its head, Yuliia Pavytska, has also been pushing the EU for a lower price cap on Russian oil and the use of more vigorous methods to stop the “shadow fleet’s” ability to circumvent the imposition of the price cap.

We currently have a situation where hundreds of oil and gas transport ships used by Russia have been targeted by the UK, EU, and NATO. These ships, for the most part, use the Baltic Sea as their departure point and where there has been a recent build-up of NATO naval forces primed and willing to view any of them as potential saboteurs of undersea cables. We also have a situation where the Nordic and Baltic countries, pushing to assert their ongoing independence from a Russia that still exists in their historical imagination remain eager to prove their mettle against that ancient foe. If we throw the Kiev regime into the mix with its ongoing determination to widen the conflict as its only way to escape a defeat by Russia we have a highly dangerous combination of aggression, motivation, irrationality and fear and all of which is now concentrated in the Baltic Sea. In that situation it only takes a false flag operation or a simple provocation to force Russia to militarily confront the physical manifestation of the forces that currently operate a financial and virtual blockade against them.

NOTE: I have mostly made use of specialist trade and financial sources in this article. Such sources, reliant as they are on understanding the issues around which their businesses are built can usually be relied upon to provide a more detailed and accurate picture that that provided in the mainstream media.