Smoke and Mirrors.

Dave Gardner

Labour is trumpeting its vocational education policy:

“More skilled brickies, carpenters and healthcare support workers will soon be trained up as we continue our drive to get Britain working, with landmark reforms announced today (27 May 2025) that refocus the skills landscape towards young, domestic talent.

The measures, backed by a record-breaking £3 billion apprenticeship budget, will open up opportunities for young people to succeed in careers the country vitally needs to prosper. More routes into skilled work means more people building affordable homes, more care for NHS patients and more digital experts to push our economy forward. This includes an additional 30,000 apprenticeship starts across this Parliament.” (Dfe May 27th 2025).

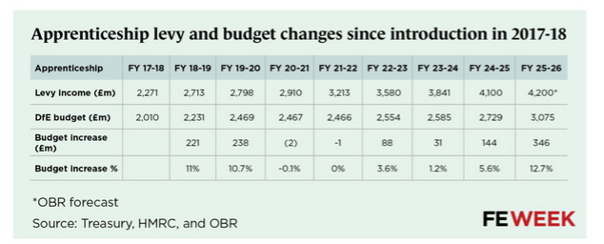

This looks good, but we need to look a little closer. Here are the figures for government spending on apprenticeships:

The £3billion that the DfE refer to is the figure in the second row of the final column above £3.075 billion. The top row is levy income paid by employers. The second row is the government contribution. It can be seen in the bottom row final column that overall expenditure on apprenticeship is up by 12.7%. £100 million comes from an automatic levy increase and the balance an increase in government expenditure of £202 million. This is a far cry from the ‘record breaking £3 billion’ that the DfE is trumpeting.

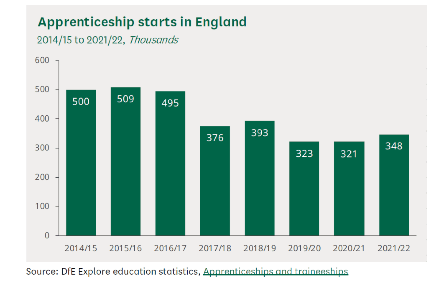

First some background on apprenticeships. They are a comparatively small proportion of vocational education in England. The great bulk of vocational education is taught through FE colleges which have not received a significant injection of new money and have only just recovered to the point that they were at when the Tories slashed the FE budget in 2011. Despite the levy, apprenticeship in England has been in decline since 2017. Here are some official figures:

The DfE tells us that there were 202,520 last year, an increase of 1% on the previous year, so we can see that the steep decline has continued from 2021-2 when starts were 348,000.

However, there are further complications. The word ‘apprenticeship’ applies nowadays to retraining of existing employees as well as training of young people. Furthermore it is normally considered to be a level 3 programme rather than a level 2, which is more of a semi-skilled traineeship. The DfE tells us that under 19s account for 27.9% (56,470) of these 2025-2026 starts, while another 76, 970 starts were on degree level programmes at level 6 or 7. So youngsters who are not eligible for or who do not wish to go to university who enter apprenticeship account for less than a third of the total of apprenticeship starts.

So what will the extra £202 million allocated by the government buy? The average per annum cost of a level 3 apprenticeship is £8655, the amount varying widely depending on the occupation, but the more technical subjects generally cost more. So we are possibly looking at an extra 23,339 new apprentices every year, a significant increase which arrests a long term decline which would amount to nearly 93,356 over a four year period. The government’s own figures suggest an extra 30,000 starts across the remainder of this parliament. That looks like a paltry 30,000 divided by 5 giving just 6,000 new starts each year. The puzzling difference in numbers probably relates to the cost of the new apprenticeships which must be far higher than the average. This would make sense if they are in technical subjects, but they would also be expensive if they include degree apprenticeships as well. One further wrinkle in these numbers is that if under 19s are only 28% of these starts this number would further shrink to 1,680 per annum and over the life of the parliament an extra 360 apprenticeships for under 19 year olds over this period, many of which will be degree apprenticeships. If we are generous however and assume that there are 23,339 new apprenticeship starts each year, this would give us around 6,500 under 19 starts from which we would need to deduct an unknown quantity of degree level apprenticeships to arrive at a number for non degree level apprenticeships. This looks better but is hardly a revolutionary change in policy and practice, rather a slowing down of a longterm decline.

Labour Affairs leaves the reader to ponder over the difference between hype and reality.